The 1965 massacres: 40 Years without Justice

17 April 2006

by Fabian Junge

In the night of 30 September 1965, a group of young military officers calling itself the “30th September Movement”, kidnapped and murdered six high-ranking Generals and one Lieutenant, allegedly to prevent a coup against Indonesia’s first president Soekarno. They dumped the dead bodies in a well called Lubang Buaya on the airforce-base Halim in Jakarta, where they had barricaded themselves. On October 1 General Suharto high-handedly took command over the army and forced the actors of the badly prepared coup to give up. In this power-vacuum, Suharto achieved his official appointment as army chief-of-staff and was mandated to restore security and order. With this, he disposed of the political, military and medial means to propagate his version of the events of September 30, which identified the Communist Party of Indonesia (Partai Komunis Indonesia – PKI) as the mastermind behind the coup attempt. In this narrative the evil, treacherous intentions of the PKI were juxtaposed with the army as the only institution able to rescue Indonesian society from the communist threat. To support these claims, the military-controlled media launched a propaganda campaign that portrayed communists as godless traitors and brutal, perverted murders. Fake reports about the mutilation of the bodies of the murdered Generals in occult sexual rituals of the PKI-associated women’s organization Gerwani (Gerakan Wanita Indonesia –Indonesian Women’s movement) served this purpose just as the alleged atheism of the communists, which was used to brand them as demons and enemies of the religion. Moreover, the coup attempt of September 30 was linked to the Madiun-affair of 1948 and both incidents blamed on the PKI. With this, Indonesia had invented its own stab-in-the-back legend.

This campaign legitimated a mass murder of an estimated 500,000 to 1 Million alleged or real communists that was perpetrated by the army in 1965 and 1966. Preceding conflicts and resentments against the PKI were used to recruit death squads and lynch mobs from the population and make them participate in the massacres. Tens of thousands of persons spent decades in political imprisonment for their alleged links to the PKI. Many of them died in the camps and prisons, and the survivors are marginalized and discriminated against until today. With the elimination of the PKI, the military had rid itself of its strongest political enemy. Now Suharto could push president Sukarno out of office and place himself at the top of the government. The trauma of the 19656/66-massacres and Suharto’s version of the evens of September 30 became a central basis of legitimacy for his military dictatorship that lasted until 1998.

This article describes the fate of three victims of the events of 1965/66, their political imprisonment and subsequent discrimination and social exclusion. It is the result of three interviews that were conducted in Jakarta in September and October 2005.

Surati Djaswadi: “My Only Hope Is for My Grandchildren to Lead a Normal Life”

In 1965, Surati Suparna binte Djaswadi, born in 1925, lived with her husband and eight year old daughter in Solo, Central Java. As a teacher and member of several civic organizations, she was a well-respected member of her community. But the hitherto simple and harmonious life of Surati and her family was destroyed by the events of 30 September 1965 in far-away Jakarta. In October 1965, large numbers of army troops under the command of Colonel Sarwo Edhie Wibowo arrived in Solo and began to arrest ordinary men and women to detain them in the town hall. Among those arrested for their alleged affiliations to the PKI and the coup attempt of September 30 were many of Surati’s friends and fellow teachers. She and her husband though did not worry about their own safety as they felt they had not done anything wrong. As they later discovered, however, they and millions of other people in Indonesia would all have reason to worry.

On the night of Oct. 16, a group of armed youth came to Surati’s house asking for her husband. As he was not home, they ordered her to immediately follow them to the Subdistrict director’s office. With surprise, Surati noted that the youngsters were masked as she recognised all of them as her former pupils. When they arrived at the office, several policemen in civilian clothes awaited her and took her to the sectional police station. The policeman who interrogated her there was an acquaintance of Surati and tried to calm her down: “The situation now is not safe,” he said, “so we have to protect you. Tomorrow I’m going to bring you to the town hall.”

Hence, on the next day, Oct. 17, Surati picked up her daughter, who had spent the night with a neighbour, and they were detained in the town hall. There she met her husband, who had been detained as well. According to Surati, the number of detainees grew to more than 1,000 persons over the weeks. Most of them were simple people: labourers, peasants and petty merchants. Many of them were teachers, too. The detainees were guarded by paramilitary youth groups under the command of Colonel Sarwo Edhie, the army colonel responsible for many massacres of alleged PKI members and conspirators in the coup attempt of September 30, especially in Central and East Java.

Soon after she moved into the town hall, Surati heard stories about the torture of male prisoners. With horror, she learned about the torture of a friend, the principal of a reputable senior high school, who was maltreated with a sickle and forced to give a false confession about his involvement in the coup. After she had been detained in the Solo town hall for one year, she was moved to a prison in Ambawara in Central Java where she was detained for about five years. The prisoners here consisted of other teachers, students as young as 12 years old, university lecturers and other members of the intelligentsia. During her whole detention, Surati was never brought before any court, was never found guilty of any crime and was never told why she was being detained. In the military-run camp, the detainees lived in poor conditions in barracks of 50 to 70 people. They suffered from the harsh treatment and arbitrary punishment of the guards. In addition, the barracks were dirty, and there were insufficient sanitary facilities. Moreover, the daily rations of food never satisfied the prisoners’ hunger. They survived mainly because some prisoners, like Surati, were sent food from their families and shared this with the other detainees.

Soon after her arrival in Ambawara, Surati received news that all her property had been seized. Government officials had taken her furniture and other items, and the small petrol station she and her husband had run had been dismantled and taken away. She also learned that her house was now inhabited by a civil servant. Fortunately, some neighbors managed to save many of her important documents.

Discrimination and Hardship after Imprisonment

While Surati was detained until 1971, her husband, who had been moved from the town hall to the Sasanomulyo prison in Solo, was released in 1968. He and their daughter visited Surati as often as they could. They were allowed to see each other only from a distance. A barbed wire fence forced them so far apart from each other that they could communicate only by shouting.

After her release in 1971, the small family had to rent a room in a boarding house. Her husband had not been allowed to return to his work as a teacher after his release in 1968 and now worked as a car washer. Upon her return, Surati was issued a special identity card that indicated she was a former political prisoner; and for several years, she was obliged to report monthly to the Subdistrict director. Until today, she has to renew her identity card every five years, unlike ordinary Indonesians aged 60 years or above who receive a lifelong identity card. Meanwhile, Surati found, just like her husband, that she was not allowed to return to her former profession as a teacher, and thus, she had to find other ways to make a living.

Fortunately, her friends helped her by giving Surati food and money. Later they helped her find work – first by selling rice, then in a textile factory and later they supported her so she could open a small kiosk on the side of the street selling food and newspapers. Surati and her husband struggled hard to support themselves and their daughter. Their efforts to support themselves were not made any easier when they discovered they had to pay higher school fees than other families for the primary education of their daughter. Moreover, during her first semester of secondary school, she was dismissed because of the background of her parents as former political prisoners. Even today the thought of this injustice saddens Surati. “They told me not to be angry,” recalls Surati, “but, of course, I was. This is unjust. I always treated the school staff with respect, and I fulfilled all my obligations as a good citizen. We are not PKI. I suffered; my child suffered. My only hope now is for my grandchildren to lead a normal life.”

Although she was not allowed to return to her former workplace, Surati never received an official letter of dismissal. In 1980, she wrote a letter to the minister of public welfare demanding her rights as a civil servant and teacher as well as official clarification of her status as a civil servant. She also asked the Deptartment of Education and Culture, the village head and Subdistrict director, but they all refused to be responsible for her.

Today Surati lives in Jakarta together with other women who became political prisoners in the wake of the 1965–1966 massacres, and she is actively involved in the advocacy of her rights and those of other victims of this tragedy. When asked what justice would mean for her today, she stresses that “the government should rehabilitate us; compensation is not so important.” She wants to be treated equal before the law and administration, wants her status clarified and her reputation to be restored. Moreover, she wants to be cleared from the PKI stigma and hopes for equal opportunities for her grandchildren. She does not want another generation to face the same discrimination she has had to endure.

Anwar Umar: “I Do Not Want to Die without Meaning in My Room”

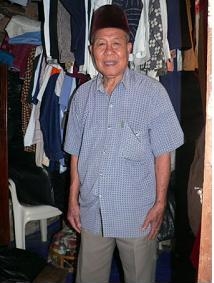

- Anwar Umar in front of his room

Foto: Fabian Junge

Anwar Umar was born in 1929 as the sixth child of a farmer in a village near Lampung, Sumatra. During the Japanese occupation, he joined a paramilitary group and participated in the independence struggle. In 1950, he went to Jakarta to where he soon found work in the civil service. He married in 1951 and became the father of eight children. After 14 years in Jakarta, during which he had joined various political organisations, he returned to Lampung to become an assistant to the governor of the newly established Lampung Province. Soon he was elected to secretary-general of the Lampung division of All-Indonesia Labor Union, a non-partisan trade union. Although he admits that the union’s interests were similar to those of the PKI, he stresses that he never formally participated in any political party.

Arrest and Imprisonment

Soon after 30 September 1965, the police and military began arresting alleged PKI members in Lampung. Although Umar was not a member of the party, a district leader close to him advised him to leave for Jakarta and go into hiding.

On October 23, Pak Umar left for Jakarta to live in the area around the Government Printing Office. After he arrived late at night, a man from the neighbourhood office (Rumah Tetangga/Rukun Warga – RT/RW), ordered Umar to his office. When Umar arrive there, he was met by a group of military officers and several other men who had been summoned. At gunpoint, the officers ordered him to sit down, and one of them shouted, “Who of you is Anwar Umar?” After he had shouted several times, Umar stood up and identified himself. He was then taken to the Mis Tijijih Building in the Pasar Senen area of Jakarta where he was detained the night. This was the beginning of an 11-year nightmare of imprisonment under degrading and inhumane conditions.

Not knowing why he had been arrested, he was moved to Jatinegara Prison the next morning, which was guarded by a unit of the military police. The first few nights he had to sleep in the open prison yard with about 800 other detainees. When the number of prisoners swelled to what Umar estimated to be 3,000 persons during the next three days, he was moved into a cell. With 60 persons per cell, the prisoners could only stand. Some prisoners in the hot and stuffy cell even drank their own urine as no drinking water was provided.

After several days, they were moved to Cipinang Prison. In the hot afternoon sun, they were ordered to strip down to their underwear and crawl into their cell on all fours. Whoever looked back was kicked by a guard with heavy military boots. Overcrowding was again a part of prison life with about 45 prisoners per cell. For one week, Umar and his cellmates were left to themselves without any food or water. After one week, his family discovered where he was detained and visited him. They brought him food and water, but Umar felt sad that there was not enough to share with all of his cellmates.

Moreover, after several days at Cipinang Umar was physically tortured, an experience that was to leave a wound on his mind for the rest of his life. On the day his torture began, he could already hear the heart-wrenching screams of a woman in great pain as he passed through the prison yard. He was led into a separate room where police officers bound his hands with electric wire that was connected to a 20-volt battery. They then tortured him with electric shocks, causing him such pain that Umar screamed and cried and his whole body trembled. After this torture he was ordered to sign a false confession which stated that Umar had been a PKI-courier between Lampung and Jakarta and that he had conspired to murder five generals. Strangely, the document did not mention the names of these generals. Umar was confused as at that point was not fully aware of the events of September 30.

When he refused to sign the document, he was brought into another room where about ten police and military officers, as well as a public prosecutor, awaited him. They immediately started beating and kicking him severely. One police officer even hit him with a chair until it broke under the weight of the blows. Another officer then grabbed his head and hit it against the wall several times. Bleeding, bruised and hardly able to walk, Umar was brought back into his cell. There, a friend who was a member of the Central Committee of the PKI, whispered to him: “Sign it [the confession]. It is better than dying or being an invalid for the rest of your life. Later we will bring the case to court, and everything will work out fine for us.” In the end, Umar took the advice of his friend and signed the confession.

He was never brought before a court, however, and was never given an official, legal verdict. Instead, he was soon moved to Tangerang Prison where he was held until 1976. Like the other prisons where he had been held, conditions in this prison were poor. The rice for the prisoners was mixed with glass splinters or sand so that many prisoners died of internal bleeding or malnutrition. “The food they gave us was only intended to make us die slowly,” recalls Umar. In order to survive, he tried to clean his rice and separate it from the glass or sand. Nevertheless his health deteriorated. When he was to be deported to Buru Island, it was only because he suffered from malnutrition, malaria and hepatitis that he did not end up in this infamous concentration camp. Instead, he was brought to a prison in Salemba where he received medical treatment. After six months, he was returned to Tangerang Prison. Now he and his fellow prisoners had to work for a farming and animal husbandry project, the revenue of which was for the military. For his labour, Umar received no compensation except for some extra food.

Life after Imprisonment

Umar was released on 26 September 1976, after receiving a letter from the “Command for the Restoration of Security and Public Order” signed by Captain Sudomo. For another three months, he was put under house arrest. Afterwards, he was not allowed to leave Jakarta for six months and had to report to the military police weekly. When the period of his house arrest concluded, he moved to Rawasari in East Jakarta.

Although Umar worked as a civil servant for more than 12 years, he never received a pension. His identity card bore the label ET (Eks Tahanan Politik – Former Political Prisoner), which branded him a communist and traitor in the eyes of the State and larger part of society. Because of this status, he was denied access to further work in the public service sector and lost his right to a pension. Hence, Umar had to survive on casual labour.

He was also subjected to the surveillance of the RT/RW. For example, he had to report when he received visitors and was not allowed to receive or talk to foreigners coming into the neighbourhood. He faced discrimination not only from the person in charge of the neighbourhood but also from many of his former neighbours who related to him with distrust and hostility.

One of Umar’s bitterest experience after his release, however, was the rejection of his family. His wife had stopped visiting him in prison after several years. After his release, Umar returned to the house of his family, but soon learned that his wife had married another man in the belief that he had been sent to the Buru Island prison camp and died there. She did not want him to live with her again. In rage, Umar was about to physically harm his wife when his eldest child and neighbours separated them. Since then, Umar has lived alone and has had no contact with his wife, although they were never formally divorced.

Because he has been unemployed for a long time, Umar today depends on the good will of people in his neighbourhood or at the human rights group KontraS where he works as a volunteer. He lives in poverty by all standards. The room in a back alley of Jakarta he calls his home measures only five square meters, and lacks sufficient sanitary facilities as he receives water to wash and cook from a well. Nevertheless, Umar continues to struggle against political injustice, not only against him and the victims of 1965, but also on behalf of others who suffered under the Suharto regime. Asked what justice would mean for him today, Umar first names rehabilitation, which would include the end of all discriminatory practices against former political prisoners. For example, he wants a lifelong identity card, just like every other Indonesian citizen above 60 years of age, instead of being required to renew his identity card every five years. Moreover, he insists that the government clarify the historic events surrounding the 1965 tragedy so that he is no longer considered unpatriotic and a traitor by society. Lastly, he demands compensation for his life of suffering. To realise these demands, he vows to continue his search for justice:

“I want to keep on fighting—for myself and for others. If I die, I do not want to die without meaning in my room or on my mattress. I want to die in the middle of struggle between my friends. This is my biggest hope. I do not desire anything else.”

Sumini: A Day at Work Ends in Nearly 10 Years in Prison

Sumimi, daughter of a policeman and homemaker in a family of six, was born in Banyumas in Central Java and schooled in Sukabumi. With an education up to the secondary school level, she mostly held administrative jobs. She began her active role in Gerwani in 1954 and even became the director of Gerwani’s office in Wonosobo.

On 17 November 1965, an officer from the district military command (Komando Distrik Militer – Kodim) came to Sumini’s office and asked for her husband, a secretary of the Indonesian Peasant’s Front (Barisan Tani Indonesia – BTI). As he was on a family visit in Bandung, the officer requested Sumini to come to the Kodim office to give her statement. He did not tell her though why he needed a statement. He promised her that she would be back home soon. But instead, this was the first day of almost a decade of detention for Sumini. Sumini met her husband in the same detention centre one-and-a-half weeks after her unlawful arrest. That was the last time she ever saw him. During the following months, she heard that he had been transferred to Wonosari in Yogyakarta Province where one of Sumini’s relatives was the last to see him. Sumini’s husband and thousands of others were rumoured to have been discarded at the infamous Luwung Grubuk, a water drainage pipe that ran directly into the sea. No one was ever shot there but rather was blindfolded with their hands bound with wire, thrown into the luwung (drainage pipe) and then sucked into the ocean.

Sumini herself was transferred to Wirogunan in Yogyakarta Province and then again months later to an all-female detention centre in Bukit Duri in Semarang, where she remained for nearly ten years. The closest she ever got to a trial or any other process of justice was in the early days of her detention in Wonosobo when a public prosecutor brought her to an orphanage to be interrogated. He accused her of attempting to alter the state ideology Pancasila and taking part in a three-month military training programme in Lubang Buaya. Sumini only offered negligible verbal opposition during her interrogation for fear of being tortured or raped or falling prey to any of the other oft-heard notorious punitive actions. Moreover, she suffered from being separated from her family. Her children were not allowed to visit her. They were even told repeatedly that their mother had been killed after she was transferred from Wonosobo. It was only good fortune that Sumini’s cousin worked at the same detention centre in Jakarta and helped inform her family that Sumini was still alive. There were no other investigations to support Sumini’s defence until February 1974 when officials from the World Health Organisation (WHO) probed into the matter.

Life after Imprisonment

After her release Sumini struggled hard with the loss of her husband, unemployment and social stigmatisation. She tried to search for her husband in several detention centres but to no avail. Her former civil servant registration number (Nomor Induk Pegawai – NIP), as well as her job at the government office where she had worked before joining Gerwani had been taken over by new personnel as though Sumini did not exist anymore. She, however, never received any monetary compensation for the loss of her position years ago, much less any compensation for her detention in prison. She had to set up a food stall by the street to sustain herself and her family, at least temporarily. The support she received from her extended family and fellow church members did alleviate some of her hardships, but life was never the same again.

Sumini, Umar, Surati and unnumbered other Indonesians lost a good portion of their life to the obscure and murky politics of the time. Indonesians under Suharto not only had to fear being labelled as communists because that was not the only excuse for a person to be arbitrarily arrested and imprisoned. As these three stories have shown, as long as one was regarded to have questionable political affiliations, they could unjustly suffer for years without any legal structure to protect their rights. <>