Carbon dealers – Papua and Aceh

28 September 2007

Marianne Klute

Aceh and Papua have taken the initiative in Indonesia against global warming: They want to limit the destruction of tropical forests and thus reduce greenhouse gas emissions. They are negotiating finance mechanisms for forest protection, and Aceh has even decided to impose a logging moratorium. Nobody can predict whether those steps will lead to success. Two things are certain: They are challenging Indonesia’s climate and forestry policies, and they will cost industrialised nations a great deal of money.

Roundtable: Climate Change

Informed readers will know that Indonesia is the third biggest emitter of greenhouse gases worldwide, after the United States and China. The causes are annual forest fires, emissions from peat drainage and fires, and rampant deforestation, which is happening at a faster pace than anywhere else in the world. Indonesia is therefore subject to intense criticism during climate debates. Given that the UN Climate Change Conference of Parties to the Climate Change Convention (COP 13) is due to take place in Bali in December 2007, Indonesia is under acute pressure to act. In Jakarta, hardly anybody seems to be concerned with preparing for COP13, whilst Jayapura and Banda Aceh show determination to act.

As part of the preparations for the UN climate conference, a high-powered Three Governors’ Roundtable was held in the upmarket resort of Nusa Dua in Bali. It was attended by Barnabas Suebu (Governor of Papua), Irwandi Yusuf (Governor of Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam) and Abraham Aturui (Governor of Papua Barat, before April called Irian Jaya Barat). The organisers and sponsors of the Roundtable included the Australian government, the World Bank and some other organisations such as Flora and Fauna International (FFI) and World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF).

On the agenda was nothing less than a common policy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The governors decided to make economic development in their provinces more environmentally friendly and sustainable, primarily by reducing deforestation. They hope to achieve this through some remarkable measures: Aceh agreed to stop logging. The moratorium which was announced has now been enacted. Through a logging moratorium, Aceh hopes to gain time for revising its forestry policy. Papua is determined to outlaw the export of wood. Suebu and Aturui did not have the courage to follow the example of Aceh and ban logging completely. For the time being they plan to examine concessions and, if necessary, revoke them if they cannot change the local forestry industry for the better in the two Papuan provinces.

The most important result of the Roundtable is the decision, to protect part of the forest from destruction. The initial idea was to protect half of the ten million hectares of ‘conversion forest’ which Jakarta seeks to ‘convert’ to plantations and to maintain those with the help of carbon finance. The original plan, however, had to be scaled down. The decision was to protect not five but just one million hectares. Several pilot projects are planned in the provinces, covering at least 500,000 hectares of forest in Papua. If they succeed then Suebu promises to expand the area to four million hectares.

In order to realise those hopeful plans, Papua and Aceh require international support in the form of finance according to the carbon trading model, as well as technology transfer. The aim is a new model of ‘Avoided Deforestation’, in which money is paid not for afforestation and reforestation, but for protecting natural forests. The Australian government has promised $AS 200 million for avoided deforestation, afforestation and for sustainable forestry. A large proportion of the money, however, will be paid via the government in Jakarta, not directly to Aceh and Papua.

The Governors’ Roundtable sends a clear signal to the international community that Indonesians are aware of the international climate debate and their own responsibilities. Aceh and Papua demonstrate the firm will to finally put an end to deforestation. Not without good reason, since the governors confirmed in a joint declaration: „We are aware of our special role as stewards of Indonesia’s largest natural forests”.

Aceh and Papua: Conflict in the Forest

Aceh and Papua are often mentioned in the same breath when speaking about Indonesia’s conflict zones. The two regions are several thousand kilometres apart, but they have some things in common: Rich natural resources, a geo-politically important position and a long history of wars and independence dreams. Indonesia’s westernmost province, Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam, and the two Papuan provinces (Papua and Papua Barat) furthest to the east also have rights under Special Autonomy laws.

Aceh and Papua have a lot more in common: They harbour the last large connected rainforests in Indonesia. Those forests, however, are no longer intact. The conflicts exacted a heavy price from the forest. It is not at all true that the forests only exist because wars offer a certain protection, as some authors claim. Quite the opposite: In Aceh, both conflict parties financed their arms with tropical timber.

Both areas also share the fact that illegal logging has greatly increased in recent years. Since the 1990s, when Aceh was a military operation zone, forests are being mercilessly cut down. Following the tsunami, pressures on the forest have grown frighteningly. The forestry ministry has granted logging permissions to five companies „for the reconstruction of Aceh”. A large part of that timber never reached the areas affected by the tsunami but founds its way, via Medan and Malaysia and Singapore onto the word market. This is why the market in illegal construction timber from the Leuser ecosystem is blooming in neighbouring regions.

Papua has been favoured by an international timber mafia. Companies from all over South-east Asia and East Asia flog off tropical timber, in particular Merbau, to the 500 new timber factories in Hainan Province which in turn sell it on to most parts of the world. There is no doubt that the army in Papua cannot be overlooked amongst the players in the tropical timber business. There are multiple reasons for the abrupt start of the Run on Papua: Elsewhere in Indonesia, tropical forests have become almost a rarity. Decentralisation opened the door widely to an even more brutal destruction of forests. When China prohibited logging in its own territory, following the Yangtze flooding in 1998 (almost at the same time as Suharto’s resignation), they had to look abroad for supplies: To Papua, Russia and many other countries.

Right now, the strong demand for palm oil for bioenergy and diesel is the driving force behind the destruction of the forests. Fire is often used to clear the land. The Indonesian government is pursuing ambitious plans to supply the international agrofuel market, and Papua is to provide a large part of the required land. This means that five million hectares of Papua are to be converted to plantations for agrofuel feedstocks.

Every initiative for the protection of forests as globally important carbon sinks must logically include Aceh and Papua. The Indonesian forest policy has missed the opportunity for change and has not dared to point the finger to exactly those hotspots. The Ministry for Forests continues to kow-tow to the powerful logging industry and generously hands out licences. At the same time, they try to keep the mafia in check through policing methods. Rambo-style actions, however, can only scratch the surface, not stop the trend. International efforts such as the European FLEGT process and different bilateral agreements remain ineffective. How then can deforestation be stopped and a contribution to reducing greenhouse gas emissions be made?

Gobal Trade: Carbon dioxide

„This is brilliant – one protects the forest and gets even paid for it“, says a jubilant Bass Suebu. He has seen how forests can be protected in Costa Rica, a country which he visited from Mexico, where he was Indonesia’s ambassador. Costa Rica has had success in curbing deforestation, and is promoting its ‘Payments for Environmental Services’ as a model for other rainforest nations. In actual fact, Costa Rica’s success is based on a logging ban, together with payments for ‘avoided deforestation’ that are financed through an energy tax and international donations. They have been trying unsuccessfully to obtain carbon funding: The price at which carbon is being traded is not nearly high enough to meet the cost of their scheme. Nonetheless, Costa Rica have convinced other governments and politicians, including the Papuan Governor Bass Suebu, that the carbon markets could, in future, help to protect the world’s rainforests. The Coalition for Rainforest Nations was formed in 2005. 33 countries with tropical forests are members, including Indonesia and Papua New Guinea. It advocates a model based not on regulation or logging bans, but on payments financed largely through the carbon trade, something which would require an amendment to the Kyoto Protocol. The governors of Papua, Aceh and Papua Barat strongly support this scheme. The Coalition for Rainforest Nations and their supporters, including many scientists, argue that the Kyoto Protocol contains a major flaw by failing to reward developing nations (non-Annex 1 countries) which protect their forests, even though deforestation is responsible for some 18% of greenhouse gas emissions and peat drainage for even more. The Kyoto Protocol allows industrialised ‘Annex 1’ nations to buy the right to emit more carbon dioxide by paying for projects in developing countries. This can include paying for monoculture timber plantations, classed as ‘afforestation’ and ‘reforestation’ projects (though so far only one such project has been approved under the Clean Development Mechanism), but it cannot involve protecting old-growth forests – even though a hectare of monoculture plantations stores at best a quarter of the carbon held in old-growth forests, and monocultures do not meet essential functions of natural forests, such as maintaining biodiversity, soils or the water cycle.

The call by the Coalition for Rainforest Nations that the protection of natural forests should be rewarded has therefore gained widespread support. During the United Nations climate conference in Bali this year, nations will debate about a successor agreement to the Kyoto Protocol, which will expire in 2012. The proposal submitted by the Coalition for Rainforest Nations will be debated at the forthcoming UN climate conference in Bali, under the name „Reducing Emissions from Deforestation in Developing Countries’ (REDD). The World Bank will present their planned $250 million pilot project for protecting tropical forests, which is compatible with the REDD proposals.

The three governors, Suebu, Irwandi and Aturui can thus be optimistic that the international community will approve of their strategy for ‘avoiding deforestation’. The proclamation made during their Governors’ Roundtable might set a precedent for a possible resolution at Bali in December and might lead to a binding international agreement.

Within Indonesia, the three governors have a difficult position: Right after Suebu’s election as Governor of Papua in December 2006, President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY) called him for a meeting. SBY supports agrofuels (‘bio-diesel’) as the engine of the economic development. He hopes that investments in the plantation sector will create 3.5 million new jobs. The President demanded that Papua should immediately promise five million hectares of forest for conversion to oil palms and other plantations. Suebu was annoyed. He has enough problems with the timber companies holding logging concessions, their illegal activities and what he regards as the ‚backwardness’ of his people. According to well-informed sources he said „not with us”. Papua should not become like Kalimantan, where the forest will soon be gone and many animal species are becoming extinct. It is not known whether SBY was also angry. However, he reacted instantly. By January, a huge five-billion dollar deal was clinched with China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOP) and their Indonesian counter part, PT Sinar Mas Agro Resources (SMART). The plantations were to be established in Papua. Since then other companies have declared an interest. Some of them have already successfully acquired land with the support of Jakarta and of local district politicians.

Question: Ecology or economy?

What appears as a clear conflict between ecology and economy is far more: The governors of Papua themselves have grand plans for the development of West Papua. They also bank on economic development and compete with SBY in attracting investors. Fantastic ideas have been airs, of which even cities like Berlin or London could only dream, such as a ‘sky train’. Bupati (district heads) and other local politicians copy them. Development is to financed above all with the ‘green gold’ palm oil and for that the forest has to be cleared. At the same time, some politicians seem to have understood the arithmetic of the carbon trade in no time – not just a few bupati in Papua who suddenly sell their forests not to logging companies but to carbon dealers. The governor of Bengkulu has just returned from a rather spontaneous trip to the US where he offered his forest to people in the US for the price of $2.5 billion. It could pay off financially to demonstrate to the international community that one wants to protect the forest in order to contribute to the fight against climate change.

Torn between climate change and investment policies, attractive offers might move other Indonesian politicians to think again. In the long-term, what Nicholas Stern 1 said in his report on the economics of climate change: That climate change mitigation and economic growth and development do not have to compete with each other. This would solve the conflict become economy and ecology.

Greenpeace has calculated, based on emissions from peat soils in Kalimantan, that Indonesia could earn more from carbon trading than from converting peat forests into oil palm plantations. If one also considers that plantation companies are known to the Ministry of Finance as notorious tax evaders, the state could earn more from carbon trading than from the whole of the palm oil industry. But, of course, only as long as the forest still exists.

This is what a calculation similar to Greenpeace’s might look like for Papua: Provided that one million hectares are protected under the REDD model and every year 50,000 hectares are saved from clear-cutting, Papua could earn $50 to $100 million, based on a low price of $10 per tonne of carbon dioxide. This is a sum which even an economist will not dismiss. If more deforestation is avoided, or if the price per tonne of carbon is set higher, then the result would be even better. The avoidance strategy could become profitable.

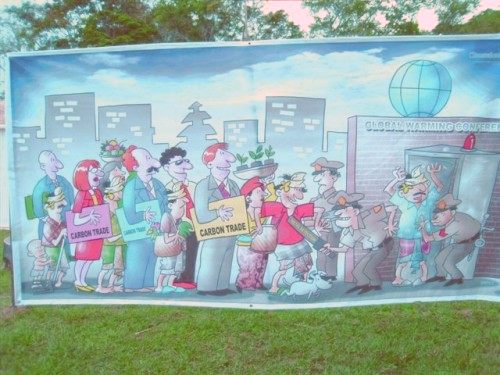

If the example set by the ‚special autonomous provinces’ of Aceh and Papua gain support then truly huge sums of money will be on the table. Big sums of money lure big crooks. Just a few weeks after the Roundtable in April, obscure carbon traders appeared in Indonesia. Criminal activities and corruption are an acute threat to society, and without a functioning administration and a corruption-free political environment, the nice economic success could become rather one-sided.

Other unsolved problems are how the funding should be managed, what special training of provincial civil servants may be required and who should benefit from the money. Should it be the plantation companies, which need to forgo palm oil profits? Should it be the government budget which, under Indonesian law, owns the forest? Or the special autonomous provinces? Or should the money go to the indigenous peoples so that they can continue to live in harmony with nature and, through their way of living, sustain the forest? And how will they deal with the social and psychological effects of this sudden monetary gain within their villages and families?

This could backfire fort the environment, too. Biofuelwatch see a fundamental flaw in the concept about avoided emissions. The biosphere has a deficit in carbon sinks, because humans release 50% more carbon dioxide than can be sequestered by oceans and by forests and other ecosystems. Given that some ecosystems are on the verge of collapse, it is not enough to conserve percentages of the forests 2.

Attractive as the avoidance strategy might sound, it will only be possible to realise it for a small fraction of the forests. If deforestation can be avoided for one million hectares of Papuan forests, that means that the other nine million hectares of ‘conversion forest’, for which no finance mechanism is being negotiated, will not be spared from destruction. According to Biofuelwatch, that scenario is not the unfortunate side effect of an otherwise beautiful concept for saving climate and forest, but an integral component of the plans for dividing our planet.

Experiment Aceh: Moratorium

Anthropogenic emissions should actually be reduced. This would logically mean conserving the forests as carbon sinks. In practice, this would mean leaving the forest as it is and banning industrial logging. A logging moratorium gives the badly treated forest a breathing space. Furthermore, as Nicholas Stern calculates in his report, the costs for administering and controlling a logging bans are of an order of magnitude smaller than those of paying for environmental services through carbon trading. This would therefore be easier to finance and to realise for the world community.

Ecosystem Earth seems to be in a fragile condition and, in view of the already destroyed carbon sinks, a systemic approach is needed. Such an approach requires that the people who live in and from the forest play a key role as environmental protectors and should be honoured as such. Basic problems need to be addressed: Land rights, the lack of recognition for the economic and social rights of indigenous peoples, corruption, and the discrepancy between the excess capacities of the wood and paper industry and the insecure supplies.

Many interests, however, compete for the forest. Not only the local people want to assert their land rights – others also want to get hold of them. Diverse industries compete for land, the pulp and paper industry wants to expand, politicians try to attract investment into infrastructure. The state is in a no-win situation: It banks on economic growth and development but deprives future generations of the foundations for either through aggressive deforestation; it suffers enormous losses in taxes and payments, has to confront increasing land conflicts and has to manage ever more frequent catastrophes.

The forest law enforcement and certification models do not work, because the roots of the evil, the basic unsolved problems within Indonesia, are left untouched. Neither EU funding for Leuser National Park, nor the EU-FLEGT (Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade) process have turned out to be suitable instruments for stopping rainforest destruction. FLEGT is restricted to voluntary agreements regarding the import of tropical hardwood into the EU and does not address growing demand in the consumer countries. Voluntary certification models offer nothing but an illusion of sustainability and often result in more rigorous clear-cutting elsewhere.

Aceh is a hotspot of the above mentioned problems and conflicts. Every year, Aceh loses around 20,000 hectares of forest. The contribution of illegal logging is high. According to the environmental NGO Walhi (Friends of the Earth Indonesia), 2.79 million cubic metres of forest were cut illegally in 2006 alone. Walhi estimate a loss of 260 million Euros, not including the costs of flooding, land slides and the ecological value of the forest. Only 2% of those huge quantities were recovered through police raids. The former GAM commander Irwandi has therefore put forest protection right at the top of his list of priorities right from his first days as Governor of Aceh. He has not shied away from personally taking part in actions against illegal loggers.

He has strong counter players. Forest Minister Kaban in Jakarta did not agree to lift the concessions for the five timber companies, quite the opposite: Jakarta exercises enormous pressure to free further forests for ‘conversion’. The government wants to increase the capacity of the pulp and paper industry in Sumatra and build new pulp mills in Kalimantan and Papua. Jakarta also sees potential for 120,000 hectares of oil palm plantations in the south and east of Aceh. The districts also plan the expansion of the timber industry and plantations – often one part of the state does not know what the other one is doing. The flow of information does not work, and the governor is facing opponents on all sides.

„Stand up for yourself” might have been Governor Irwandi’s motto when he opted for the initiative to conserve the tropical forests in Aceh and thus for a contribution to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. During the Governors’ Roundtable, he promised to do what he could to protect the forest. Clear decisions were made.

Irwandi doesn’t regard the moratorium as the ultimate goal of his forestry policy. It is supposed to be a 15-year process with different stages, a breathing space in order to reform the forestry sector. A 15-year long break should give the government of Aceh time and space to address the existing conflicts around forest and land. Whether Irwandi can succeed in managing the conflicts with the powerful competing economic interests is a different issue.

During the first stage, no new concessions will be granted and an inventory will be taken. The legal status and the physical conditions of the forest will be examined. An independent agency is to carry out an audit, based on which existing concessions should be withdrawn, if the companies involved have exceeded the powers they were granted. The time is to be used to pass legislation to allow the use of confiscated, already cut timber and to allow for necessary imports. Eight months after the first phase, all logging in Aceh is to be stopped. Wood would only be allowed to come from plantations or community forests. A logging ban has to be accompanied by measures to reduce poverty and to strengthen social and economic rights. New jobs will have to be created, including for those people who currently work on timber plantations.

However the conflicts of interest will play out, Aceh and Papua are becoming actors on the international carbon market and will earn money in the process. What matters now is how Indonesia positions itself during the UN Climate Conference. This will show whether the rainforest ‘stewards’ will become real pioneers. <>

1. Nicholas Stern: Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change; October 2006/ http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/independent_reviews/stern_review_economics_climate_change/stern_review_report.cfm

2. ‘Reduced Emissions From Deforestation’: Can Carbon Trading Save Our Ecosystems? July 2007 http://www.biofuelwatch.org.uk/docs/Avoided_Deforestation_Full.pdf