Public Commemoration for Victims of the Aceh Conflict

09 June 2010

by Fabian Junge

Five years after the signing of the peace agreement between the Indonesian Government and the Free Aceh Movement (GAM), commitments to establish a truth and reconciliation commission and a human rights court for Aceh have not been fulfilled. Nonetheless, victims of human rights violations continue to mark key events in the history of the decade-long armed conflict. Most recently, on 3 May 2010, they commemorated the so-called Simpang KKA-massacre in a ceremony that comprised public testimony by victims and the laying of the foundation stone for a monument by the of North Aceh government.

“For people outside of Aceh, the 3rd of May is a day like any other. But for us, this date has a meaning, for on this day we ran in panic, were shot and wounded, and lost many loved ones.” With these words, a member of the Association of Victims of Human Rights Violations of North Aceh (K2HAU) opened the day long-commemoration of the Simpang KKA-tragedy.

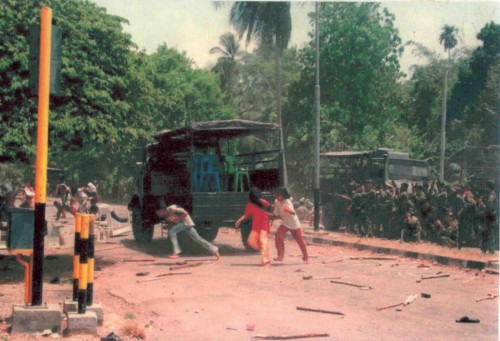

The term describes the gross human rights violations that occurred on 3 May 1999 at the junction close to the PT Kertas Kraft Aceh (KKA) paper mill, just outside the industrial city of Lhokseumawe, North Aceh, when Indonesian military units opened fire on a crowd of several thousand demonstrators, killing at least 49 people and wounding 156. During the preceding days, soldiers from a guided missile unit had entered the nearby village Cot Murong and maltreated several community-members in a search for a solider that had allegedly gone missing during a religious celebration in the village. Military and the community then negotiated an agreement that barred the former from entering the village without permission. When military officers violated this pact, demonstrators were mobilized to the KKA-junction, where the massacre occurred 1.

The recent commemoration took place at the exact location of the massacre and was attended by victims, local residents, regency government representatives, journalists and NGO-members, amounting to about 1000 people. The event aimed to honor the victims, give visibility to their individual suffering as well as to garner support for the campaign for a local truth and reconciliation commission.

At the start of the event, an Islamic preacher recited verses from the Koran and led prayers for the Simpang KKA-victims and their families. He prayed for recognition of the victims’ sufferings and non-repetition of the crimes against humanity that occurred in Aceh during the 30 year-long armed conflict. Murtala, chairman of K2HAU, welcomed the participants and pointed out the poor living conditions of most victims of the Simpang KKA-tragedy. He expressed bitter disappointment with the lack of much-needed mental and physical health care for victims, and demanded the formation of a truth and reconciliation commission by the provincial government.

A highlight of the days’ event was the public hearing of five victims of the Simpang KKA-tragedy. The hearing was led by five representatives from Acehnese human rights and indigenous organizations, who posed as commissioners in this civil society-version of a truth commission. It was modeled upon the draft legislation for a truth and reconciliation in Aceh that civil society submitted to the provincial government in 2007 – without any tangible response until today. Furthermore, the commissioners sought inspiration from public hearings conducted by the East Timorese Commission for Truth, Reception and Reconciliation.

Khairani Arifin, a legal scholar from the NGO Women Volunteers for Humanity (RPuK), chaired the hearing. Opening the hearing, she expressed her gratitude to the five testifying victims and congratulated them on their courage. The commissioners then invited the victims to recount how they experienced the Simpang KKA-massacre:

“I was 13 years at that time and lived near the KKA junction. A group of people asked me to join the demonstration there … Around midday I sat down at the crowded junction to rest. The situation between military and demonstrators heated up, and suddenly people started running. Then the military started shooting. I threw myself on the floor trying to avoid the bullets. Next to me I saw a man lying on top of his wife, hugging her, trying to protect her. He was shot dead in front of my eyes … Everything happened so fast. There was blood on my trousers but I thought it was from somebody else … After the shooting was over, people lifted me into an ambulance. Only then I realized that I had been hit … I was brought to the hospital and operated… During the first night, the wounded gathered in one room, we were afraid that the military would come and kidnap us. Kidnappings were common in our area during the conflict.”

“At the time of the incident, I was 17 years old… In the morning, my mother warned me not to go to the demonstration. But I went with some of my friends, we were curious… The junction was crowded and the atmosphere was tense. Someone shouted ‘women to the front, women to the front, they sure won’t shoot at the women.’ People started throwing rocks at the military…When they started shooting, I ran with the crowd and entered one of the kiosks at the side of the street. I lay down, but my feet stuck out into the direction of the military … When the shooting stopped, I tried to stand, but my legs had been shot. Later I discovered that there were 19 bullets in my legs…”

“My youngest child was taken from me on that day. I used to sell food at the KKA junction and on that day I was there with my nine year-old son… When the shooting started, I ran, holding him in my arms. But then I fell down and lost him in the crowd. Somehow I was pushed into one of the shops at the side of the road. There were many people hiding in there. I wanted to get outside to look for my son but they would not let me. I shouted his name. After the military left, I looked for him but was told he had been brought to the hospital. Only later I found out that he had died…I cannot forget that day. I cannot accept that my son is gone…”

“I was 15 years old then and was preparing for junior high school final examinations… That is why I went to the demonstration in my school uniform. The people there told me to go home, but I was afraid to leave alone… I was hit by the first round of shots. Half conscious, I heard continuous shooting and people shouting and screaming. I fainted and when woke up, I was already in the hospital. A bullet had hit my head and I had to be operated several times… There are still bullet splinters in my head but I cannot afford the necessary treatment… I hope that this violence will not be repeated. The government has to pay attention to us victims. There has to be a court to try the perpetrators and a truth commission. If the perpetrators are not tried, they will feel encouraged to repeat what they have done, maybe to do even worse.”

The hearing related the many facets of individual suffering in the wake of the massacre. It showed that memories of the massacre and the impact of violations then determine the lives of victims until today. Anger and sadness about their losses was strongly felt – be it the loss of a loved one, a permanent physical or mental injury, or the reduced ability to pursue one’s aspirations in life. The commissioners will prepare a report of the hearing. It will be submitted to the Acehnese government to reiterate the demand for a truth commission and human rights court.

Following the hearing, a representative of the regent of North Aceh and members of the local parliament laid the foundation stone for a monument to commemorate the victims of this massacre. Prayers and singing accompanied the ceremony, which was held at 12.30 pm, exactly the time eleven years ago when the first shots were fired. A religious leader blessed the stone. Next to the foundation stone, pictures of three different designs for the monument were displayed. In consultation with the local parliament, victims and local community members will choose one of the designs.

That the regency government has agreed to erect this monument can be seen as a success of K2HAU’s intense lobbying of the North Aceh legislature and executive bodies. This it is the first time that a local government has agreed to erect a structure that permanently recognizes victims of human rights violations in a public space. It shows that in the post-conflict power constellation, it is possible to open up space for public recognition of past human rights abuses by the state, at least at the local level.

For five years now, victims and civil society groups have struggled for a human rights court and a truth and reconciliation commission – both of which are envisioned in the peace agreement and in the national law implementing the peace process. Until today, both parties to the peace agreement have yet to take concrete measures to implement these stipulations. The civil society-led truth-telling initiative of 3 May 2010 was the first of its kind in Indonesia. It has provided room for victims to come forward and speak of their experiences in public. With their demands repeatedly ignored, victims in North Aceh have taken things into their own hands to demonstrate what a truth-seeking mechanism for Aceh could look like. <>

1 For a comprehensive summary of the incident see http://www.hrw.org/campaigns/indonesia/aceh0515.htm.